Short Distance Racing on the Chesapeake

End of Year Regatta featured Course #3 to Whitehall Bay

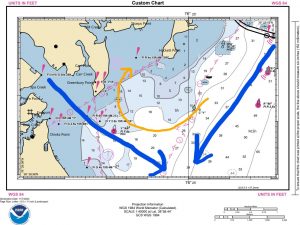

Course #3 starts near “2E”, leaves R “4” and Y “A” to port, and rounds “2W” to starboard. We started a little after 10:00 into an oscillating northerly that started at 12 to 15 knots and then moderated over the day. There was an ebb tide, with current of .3 to .5 knots from the north (335 degrees to 50 degrees). While a 1/4 to 1/2 knot of current doesn’t sound like much, it can be huge in a sailboat race — especially if a boat is able to mitigate or – better yet – benefit from current while their competitors are fighting it.

The bottom of the bay causes friction – slowing current. The rule of thumb is to be in deep water when the current is favorable and in shallow water when the current is adverse. In the graph at the right, the green “+” signs are the direction and the red line marks the current velocity. This buoy is just off the race course to Whitehall Bay 1/2 mile south of the Bay Bridge. If the current is caused by tide, it changes first inshore and then works itself to deeper water and hangs on longer there. This is one of the reasons the tankers, sitting in deep water, can point the opposite direction of the current near shore.

The other factor is bit of local knowledge. There is something known as the Whitehall Bay eddy. As the current flows down the bay in the main channel, it bumps against the current flowing down the Severn River. This causes a reverse eddy up the western shore and into Whitehall Bay. So the current will either be slack or slightly flowing in the reverse northly direction.

So what’s this all mean for our Course #3?

There are two factors here: the eddy – which favored staying close to the western shore, and the wind – which was clocking but also oscillating from a Northerly to a North Easterly. This means while the breeze was shifting back and forth it was also steadily clocking right. The wind favored going right and the current favored going left.

In these cases a sailor has to modify the adage of “always stay on the lifted tack” to something more nuanced. There is no way going out in the Bay and getting in a half knot of adverse current is going to pay off, so a sailor modifies what number of degrees suffices to force a tack. If, under normal circumstances, a boat would tack when it was headed 5 degrees, a boat might wait until she is headed 10 or even 15 degrees before flipping onto port tack and pointing the boat towards deep water. As soon as the breeze comes back left a little and we can make starboard tack work towards the mark, it is time to tack and start heading to shallow water again. The boat still tacks when headed, but it only takes a small header on port tack to cause a tack, but it takes a larger header on starboard tack to force the same result. The upwind track would look something like the green track below.

Now the problem becomes one of navigation. How does a boat stay close to Greenbury Point (Western Shore) without running aground on those 1 and 2 ft bumps? Use line-of-sight navigation.

Line-of-sight navigation means using the visual aides in the water and on shore to ascertain where you are on the water. Let’s start from when we round “A” on our way to “2W”. We want to get inshore as soon as possible so the first header we get, we tack onto starboard and start heading for shore, but how far can we go in? We can look at the chart and know that if we go in as far as “4” that would be too far and we risk running aground, but we also know if we draw an imaginary line (lime green) between “2W” and Chesapeake Harbor, we will be safe – so we sail on starboard until we get headed and/or hit that line.

We know we are safe on port tack, but we also know were are heading to deeper water and more adverse current. Looking at crab traps here could be key — which way is the current actually flowing? Eventually we get headed enough that we decide to go back, so we throw in the third tack. Now things get a little tricky as that 1 ft bump on the chart is pretty much on our bow. How do we know where that bump is? Again, we look at the chart and we can figure out where we are. We are coming into line with the southernmost tower on Greenbury Pt, we can’t see the northern shore of the Severn River, and we are approaching a line between “2W” and “A”. These are the purple lines below. It is absolutely time to tack.

We sail out on port until we get headed again. We are looking  to be almost pointing into Mill Creek before we tack back onto starboard to avoid that 1 ft bump. Eventually, we get headed and we’re pretty confident we’ll be pointing mostly towards Mill Creek when we tack, so its back onto starboard with tack number 5. We head in being cognizant of shifts and current. We know we can go in only as far as just past an imaginary line between “2W” and the northernmost tower on Greenbury Pt (yellow line below). We reach that line and tack back. We are now done with our depth issues as the Rainbow only draws 3ft, so we “play” with our yellow line and the shifts, and work our way to “2W”.

to be almost pointing into Mill Creek before we tack back onto starboard to avoid that 1 ft bump. Eventually, we get headed and we’re pretty confident we’ll be pointing mostly towards Mill Creek when we tack, so its back onto starboard with tack number 5. We head in being cognizant of shifts and current. We know we can go in only as far as just past an imaginary line between “2W” and the northernmost tower on Greenbury Pt (yellow line below). We reach that line and tack back. We are now done with our depth issues as the Rainbow only draws 3ft, so we “play” with our yellow line and the shifts, and work our way to “2W”.

On the way home – orange track – we want the deep water and to get out of the eddy so we give Greenbury Point wide berth to stay in the favorable current while keeping our jib working on the long downwind run to “A”. To stay out of shallow water we need to stay outside of the purple line between “2W” and “A”. While we don’t want to sail too much extra distance, if we err, we err on getting to deeper water.

Here are the pictures from the regatta and the End Of Year Potluck:

Leave a Reply